Google and Booking: The Symbiotic Gatekeeper Relationship in European Hotel Search

Google is likely averse to making significant user experience changes in the hotel vertical because the status quo is so profitable. Booking.com appears to be the primary driver of this profitability.

Part I: Digital Markets Act Implications

Summary

Even given its legal obligation to comply with the Digital Markets Act, Google is likely averse to making significant user experience changes in the hotel vertical because the status quo is so profitable. Booking, another European Commission-designated gatekeeper, appears to be a primary driver of this profitability.

Near Media analyzed the sessions of 300 European consumers (100 each in Germany, France, and Spain) who had granted screen and audio recording permission as they searched for hotels on Google.

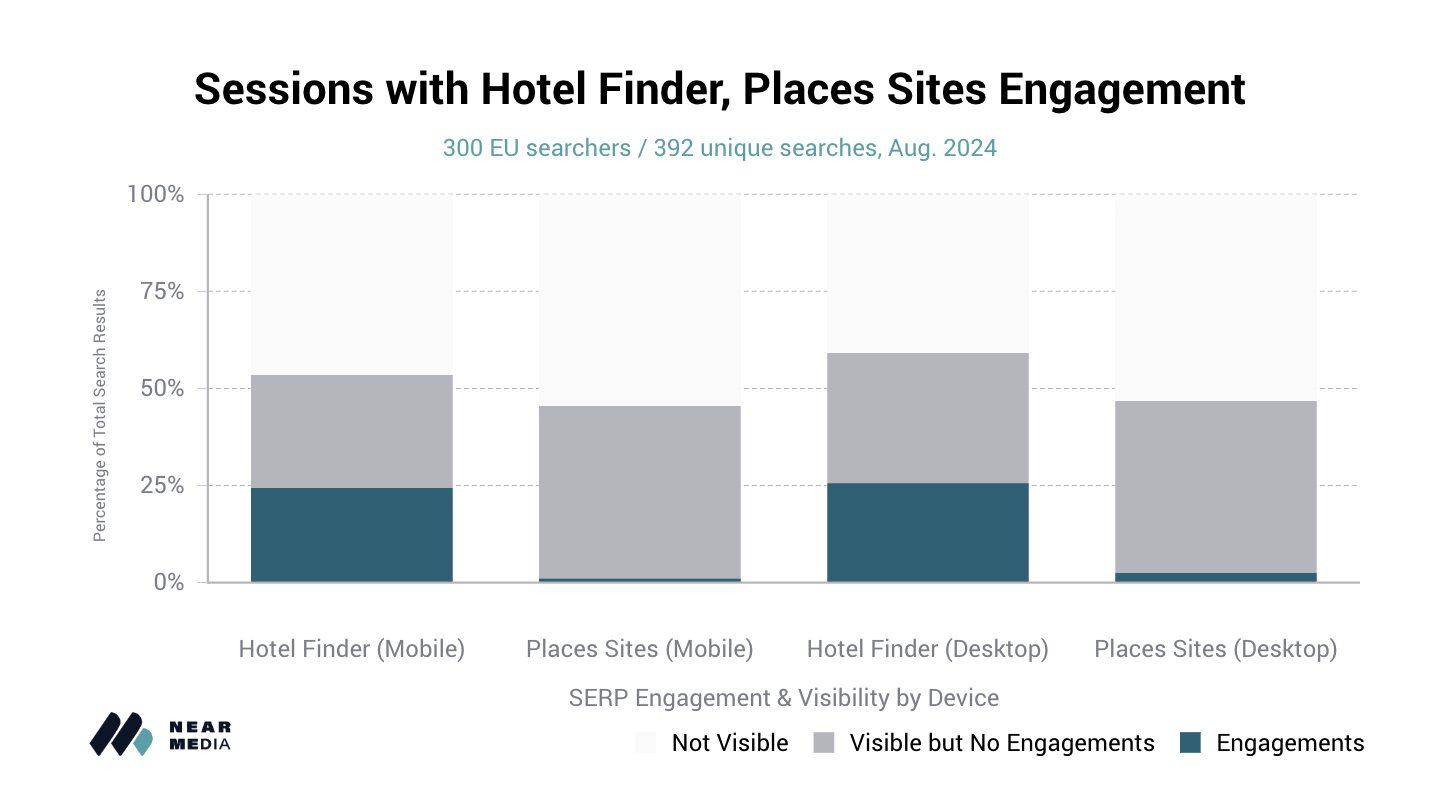

As we’ve seen in other verticals, the Places Sites module, introduced by Google as a significant component of its response to the Digital Markets Act’s self-preferencing provision, is almost never used by searchers. This module was visible to searchers for 50% of queries in this study. When visible it typically appeared in the first or second organic position, but drove just 7 out of 601 total clicks.

Google’s own Hotel Finder received clicks 56% of the time it was visible to searchers (invariably adjacent to Places Sites)–and the Hotel Finder and Google Maps garnered 28x the total number of clicks as the Places Sites module.

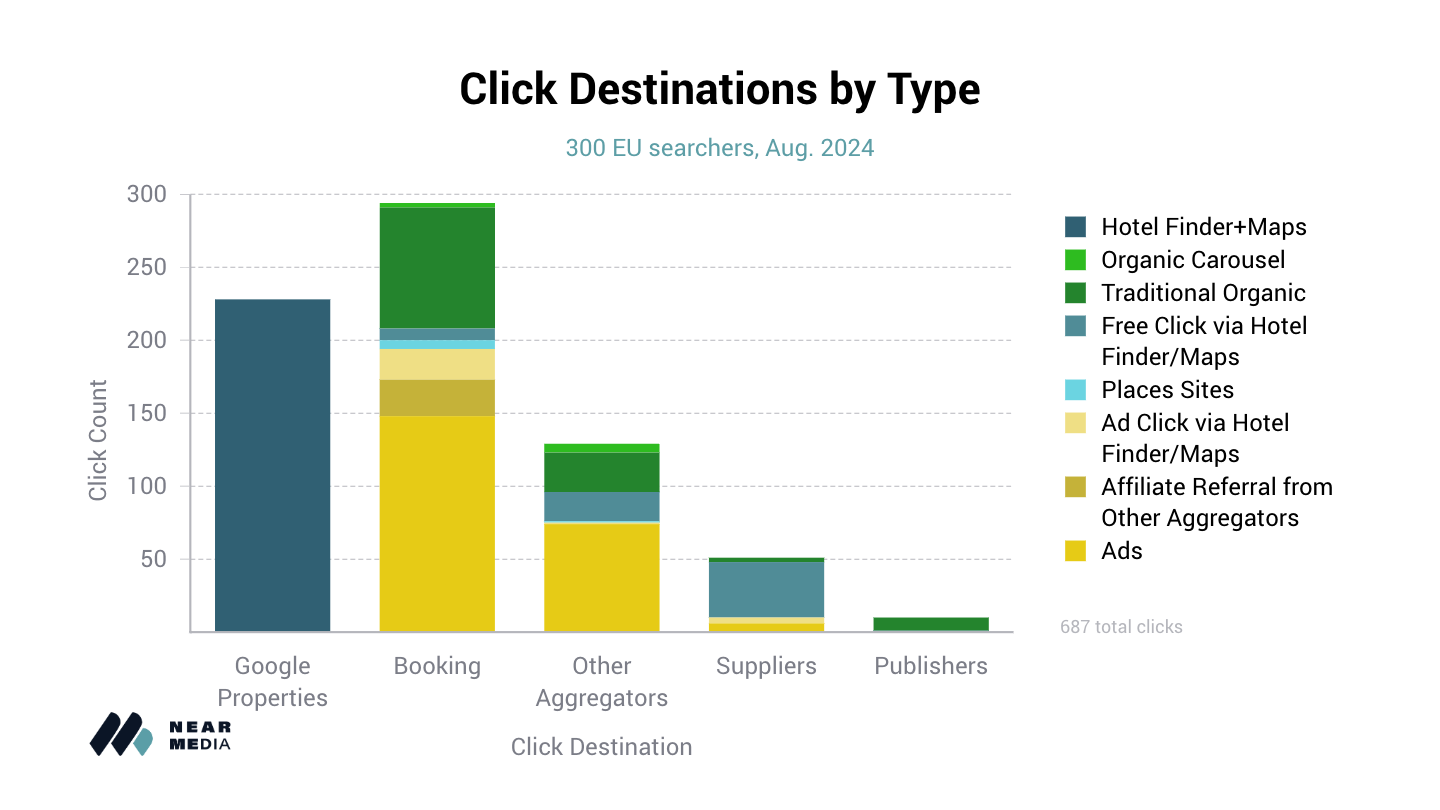

The percentage of clicks sent by Google to hotel Aggregators and Suppliers skews heavily in favor of Aggregators–in particular, heavily in favor of Booking, a designated gatekeeper subject to the Digital Markets Act.

Booking’s consistent bidding for premium ad space on Google is undoubtedly raising prices for consumers, not just for consumers who reserve a room on Booking, but on any site competing for hotel search traffic.

In all, 48% of queries (including 62% of mobile queries) in the hotel vertical yielded at least one ad click, compared to between 4%-11% queries in our previous research in other verticals, giving Google a strong financial incentive to maintain the status quo in this vertical.

Introduction

Article 6(5) of the European Union Digital Markets Act, passed in 2022, requires that digital gatekeepers (including Google’s parent company Alphabet) not treat “more favourably, in ranking and related indexing and crawling, services and products offered by the gatekeeper itself than similar services or products of a third party” and that gatekeepers “apply transparent, fair and non-discriminatory conditions to such ranking.”

Numerous software tools exist for tracking the rankings of individual websites and certain interface elements across individual Google queries and ranges of queries. Google itself reports click data to verified website owners in Google Search Console and to verified profile owners in the Google Business Profile (GBP) console.

Historically Google has kept click behavior that takes into account the entire Search Engine Results Page (SERP) to itself. Typical user interface tests using prototypes and mockups are useful proxies, but hide significant nuances found in live search experience data.

Near Media regularly conducts consumer behavioral research on behalf of enterprise clients. We applied our typical methodology to understand what impact on searcher behavior these new SERP result types would have, if any, within the E.U.

Among the questions we sought to answer:

• What search interface types received the most engagement, and by extension, did the new Places Sites module receive meaningful engagement?

• What was the balance of traffic sent by Google to Aggregators and Suppliers?

• Which Aggregators, if any, received the biggest boost from this post-DMA treatment?

N.B.:

Near Media self-funded this study.

For the purposes of this study, we considered Airbnb an Aggregator.

A visual glossary of many EU SERP elements can be found here.

Methodology

To answer these questions, we recruited a panel of 100 residents each from Germany, France, and Spain and presented them with a hotel search scenario, recording their screens and narrations with permission.

We then analyzed and aggregated their search behavior, narrated in their native language. Participants were split evenly across Desktop and Mobile devices.

We gave our panel the following instructions in their native language:

Scenario: Your best friend’s birthday is coming up on 12 October. To celebrate, they’ve asked you to go to {city} with them for a long weekend. Your friend has agreed to pay all reasonable expenses for the trip, but they have trouble with travel details and they have asked you to book hotel rooms for both of you.

You go to Google to find a reasonably-priced hotel room for you and your friend’s weekend trip to {city}. Browse and click any results you’d like. Please “think out loud” as you search and describe your thoughts and reactions.

- What results are you drawn to?

- What elements of the results stand out to you?

- Which hotel would you choose to book with and WHY?

Once you’ve found a room that suits you, please simply say “this is the room I’d choose.” Do not actually complete a booking.

(All French users were prompted with Rome as the destination; German and Spanish users were prompted with Rome or Paris.)

Results

Positioning of SERP elements

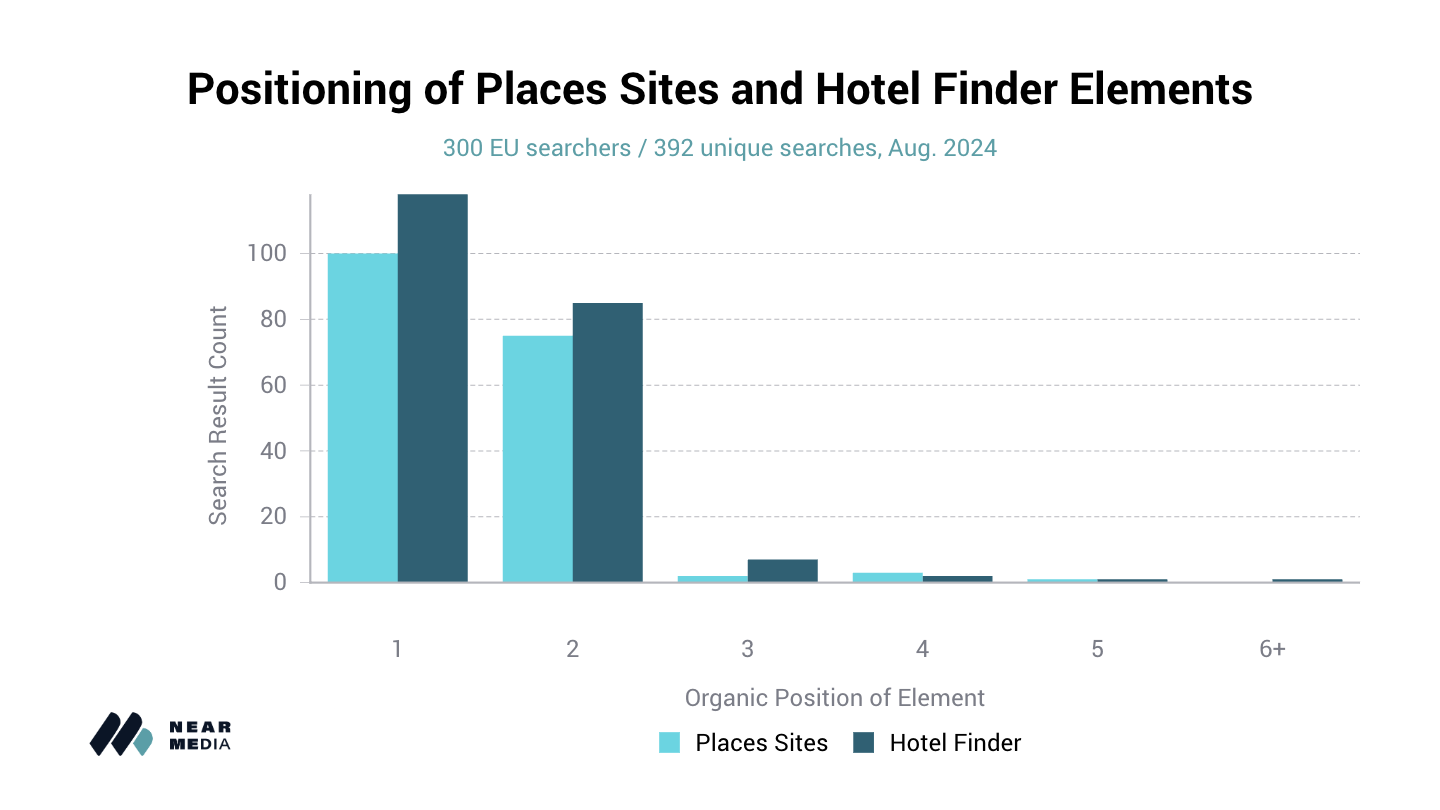

On the surface, Google appears to be giving the Places Sites module prominent billing, presenting it in either the first or second organic position 45% of the time.

However, Google continues to present its Hotel Finder either just above or just below the Places Sites module, invariably drawing searchers’ eyes and clicks to its own results with the embedded map, colorful iconography, and interactive photo elements. The Hotel Finder also appears in the top two positions 16% more often than the Places Sites module.

Engagement with Google SERP elements by device

Even when the Places Sites module appears in the top two positions, this feature has little to no impact on behavior. In fact, were it given such prominent placement, a traditional organic result would likely earn far more clicks. The Places Sites module received almost no engagements (only 7 out of 601 total clicks), mirroring the lack of engagement we’ve seen in other local search verticals including restaurants.

Our surprise in the hotel vertical was the relative lack of visibility for both the Hotel Finder and Places Sites module. In restaurants, the Local Pack of Google Business Profiles was visible to searchers almost 90% of the time, vs. just over 50% for the Hotel Finder in this study.

The reasons?

- Users rarely scrolled past the extensive ads Google showed for discovery searches (e.g. “hotels in rome”).

- We saw a significant number of brand searches for Aggregators (Booking in particular), for which Google displays neither the Hotel Finder or Places Sites module.

Engagement with Google SERP elements by position

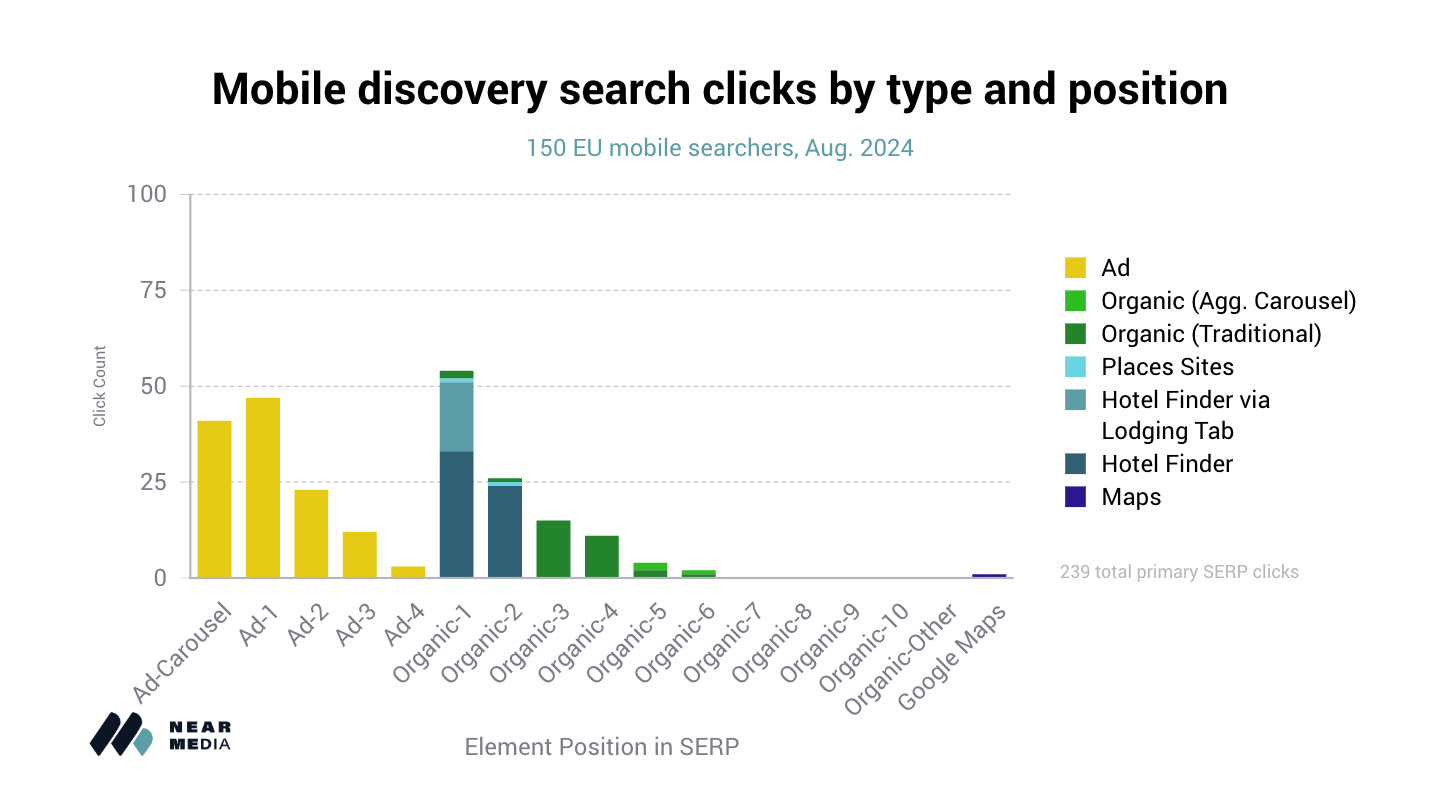

Mobile searchers were highly likely to engage with ads. This was the primary reason so few of them encountered either the Hotel Finder or Places Sites module: many did not make it far enough down the page to see them.

In fact, ads received the majority of all mobile clicks (53%), while the Hotel Finder garnered 31%. Organic results (whether Places Sites, Aggregator Carousels, or Traditional organic results) attracted just 15% of all mobile clicks.

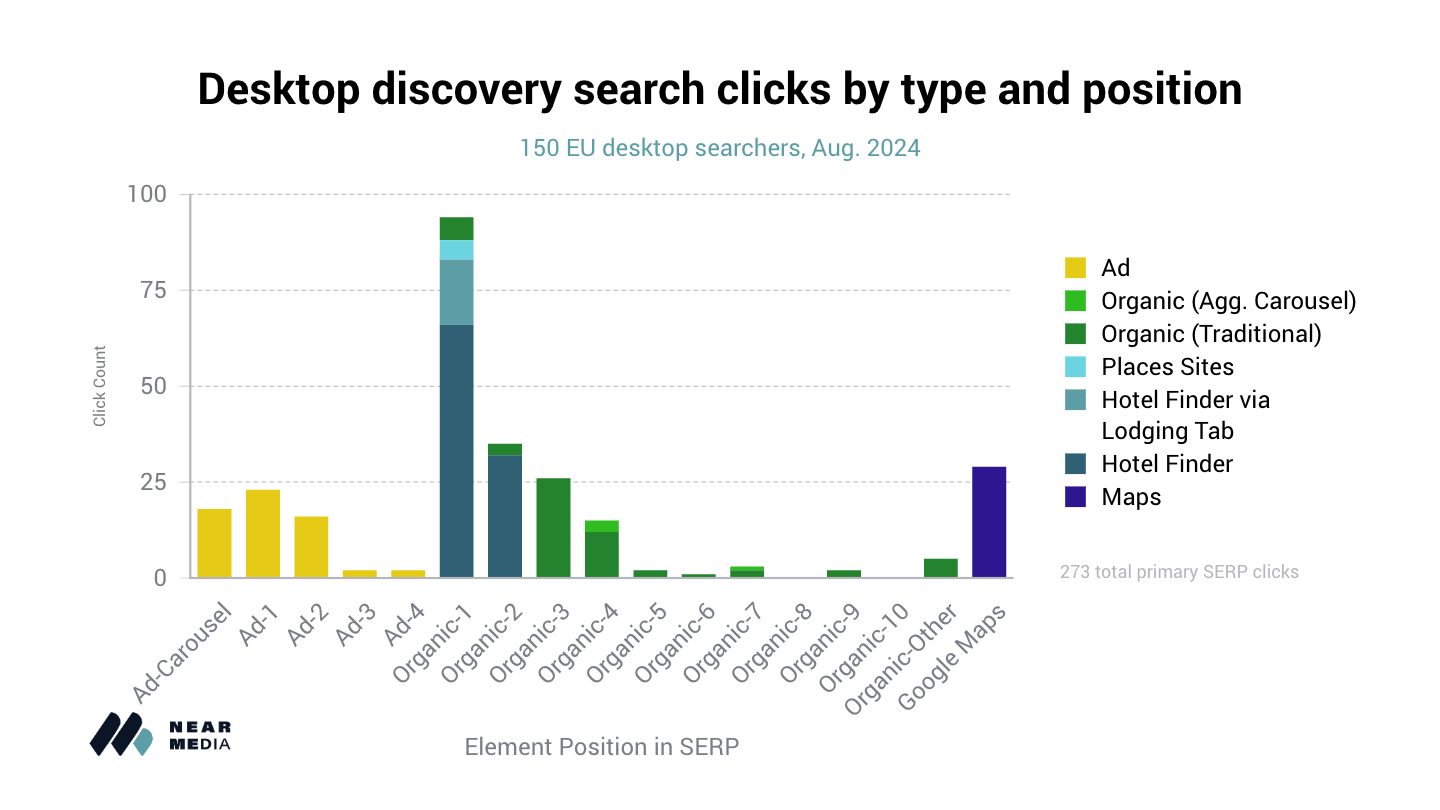

Desktop behavior hewed a little more closely to the results of our previous research. Ads received 22% of desktop clicks, while the Hotel Finder received 42%. Organic results received 25%. (7 desktop users went directly to Google Maps, which accounted for 11% of all desktop clicks.)

Engagement with Google SERP elements when the Hotel Finder is Visible

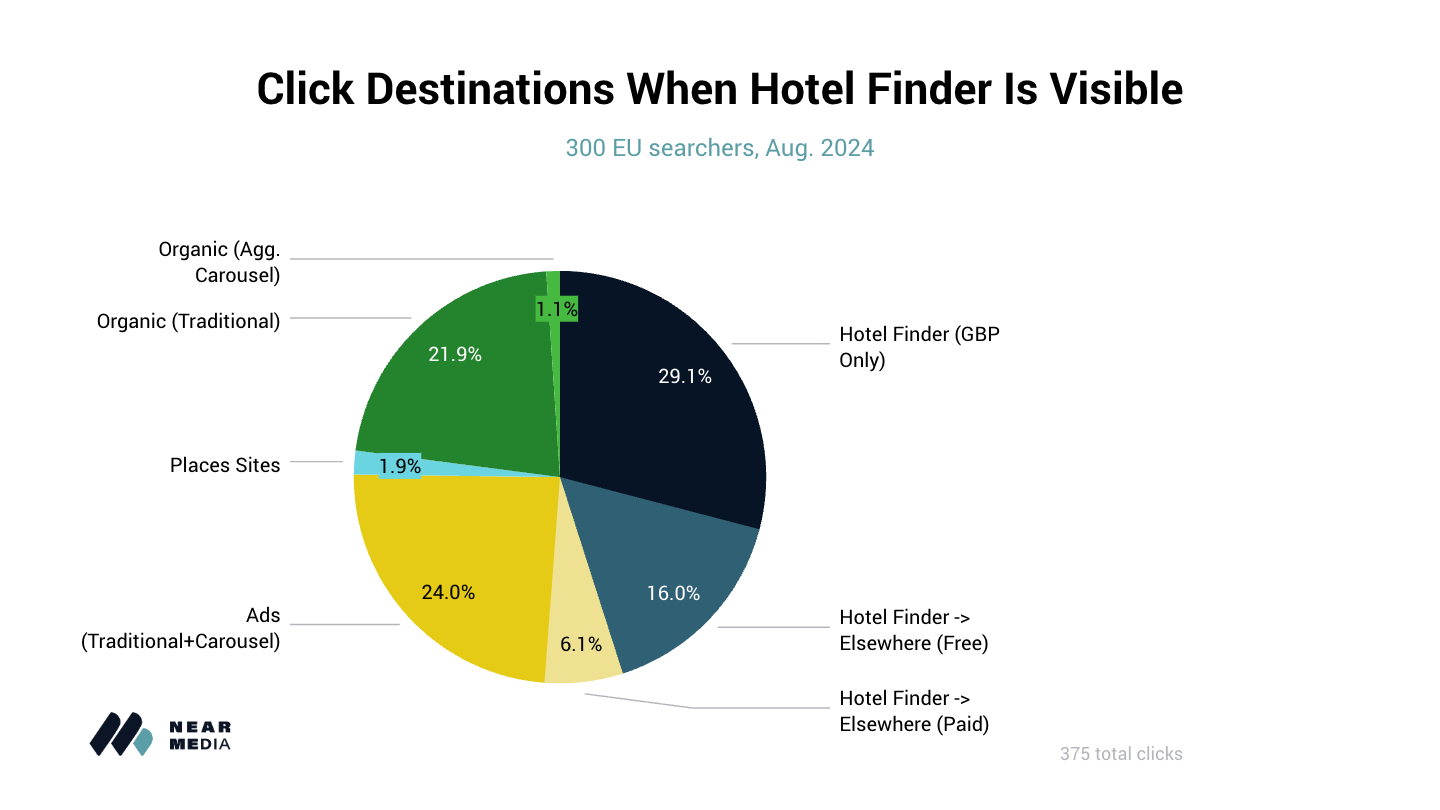

Our panel of 300 searchers made 395 total clicks within Google results when the Hotel Finder was visible.

When visible, the Hotel Finder drew half of all clicks (197/395). And half of Hotel Finder Profile views (97/197) ended up on a Supplier or Aggregator site for that property.*

Ads still drew almost a quarter of all clicks, even after the searcher had scrolled far enough to encounter the Finder.

Organic results drew another fifth of clicks, while the Places Sites module and organic Aggregator Carousel, introduced as the centerpieces of Google’s DMA compliance earlier in 2024, drew less than 2% each.

*Some consumers visited multiple sites via the same Google Hotel Profile to do more research or make a booking, hence the representation of Hotel Profile clicks totaling slightly more than 50% in the above graphic.

Engagement with Search Results by Click Destination

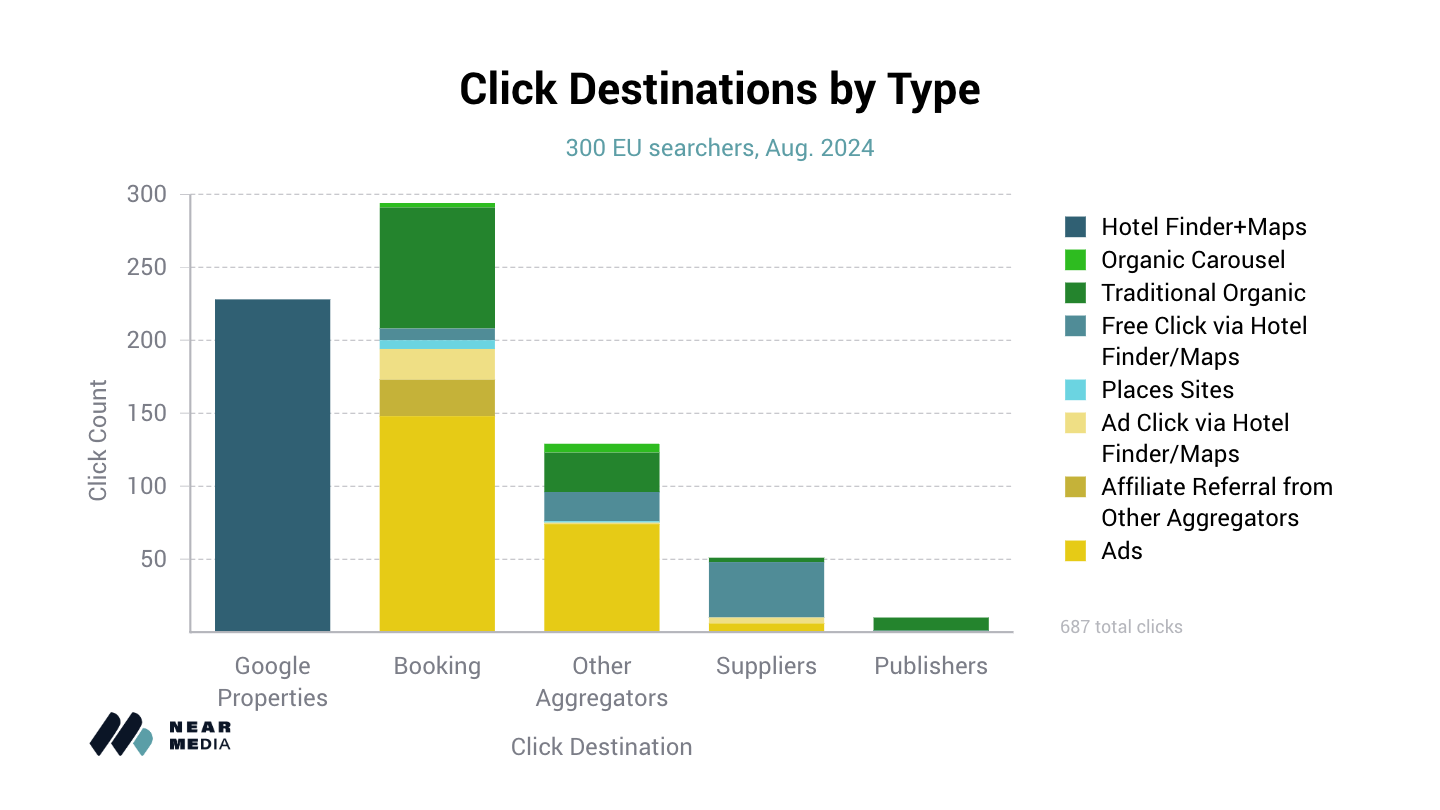

Aggregators received approximately three-fifths of all clicks, and paid for approximately three-fifths of those clicks.

Another 33% of clicks went to Google Hotel Finder Profiles or Google Maps, with consumers clicking through to Suppliers’ and Aggregators’ websites from those Profiles equally about 18% of the time. Hotel Finder profiles were the primary source of Suppliers’ traffic (almost entirely unpaid), but consumers largely used these Profiles to disqualify a particular hotel from consideration without leaving Google.

Meanwhile, nearly half of all Aggregator clickthroughs from Hotel Finder Profiles were monetized by Google (seen in the screenshot below as “Patrocinado - Opciones destacadas”).

While Suppliers are eligible to place ads alongside Aggregators in carousels, traditional ad blocks, and on Google’s Business Profile of their hotel, consumers don’t encounter them at nearly the same frequency as Aggregators.

Rarely if ever do paid Aggregator clicks from a Hotel Finder Profile or an Ad Carousel unit take users to directly the corresponding property on the Aggregator, but instead to a list of multiple properties. This increases the chance that a user will book a room on the Aggregator, even if not their original preference from the Google Hotel Finder.

Boutique suppliers don't have the same opportunity to convert a user into a different property than the one clicked from Google, making it harder for ad spend to pencil out.

Whether Google’s ad auction in this vertical is “fair and contestable,” a commonly-stated goal by many European Commissioners, is worthy of future investigation.

Differences in Search Behavior by Country

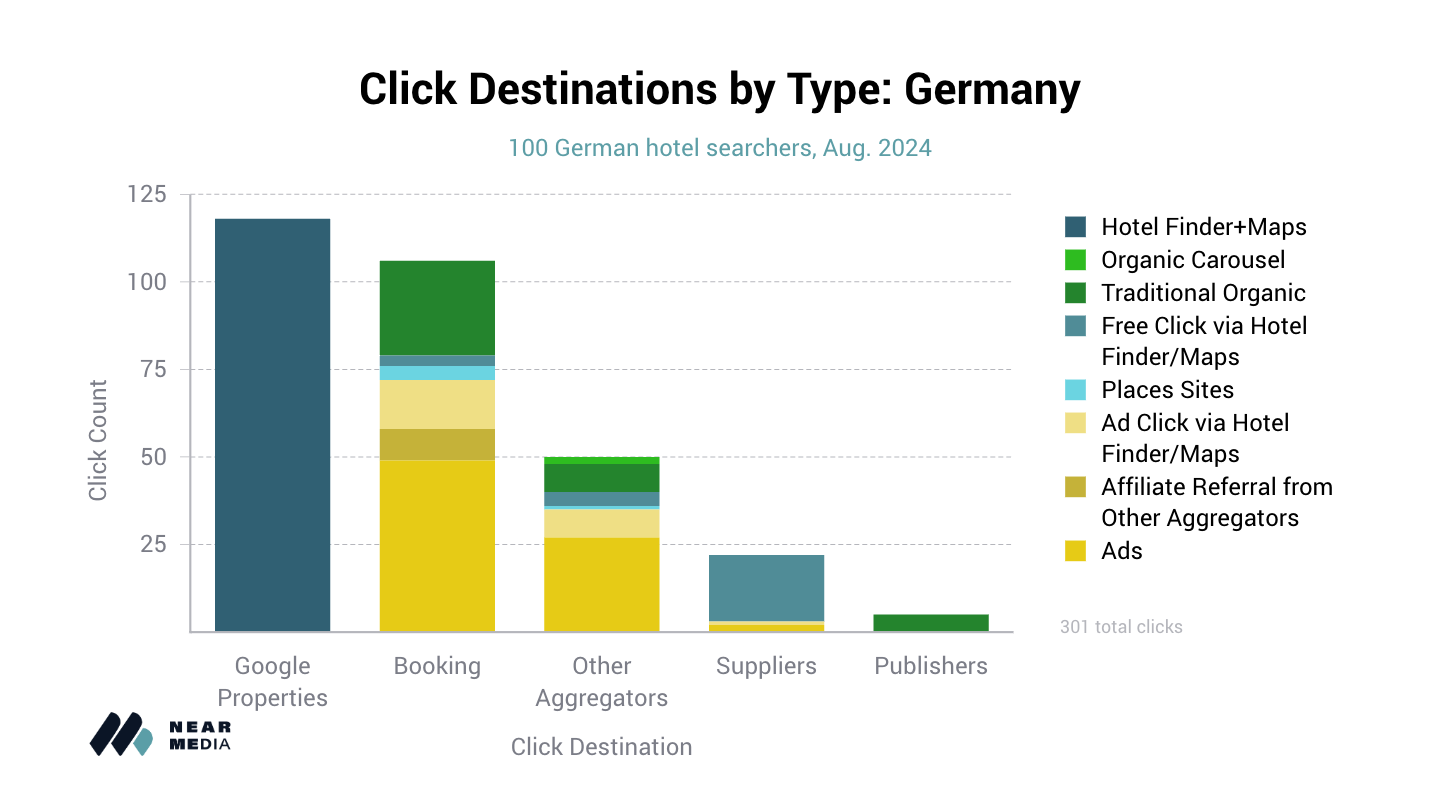

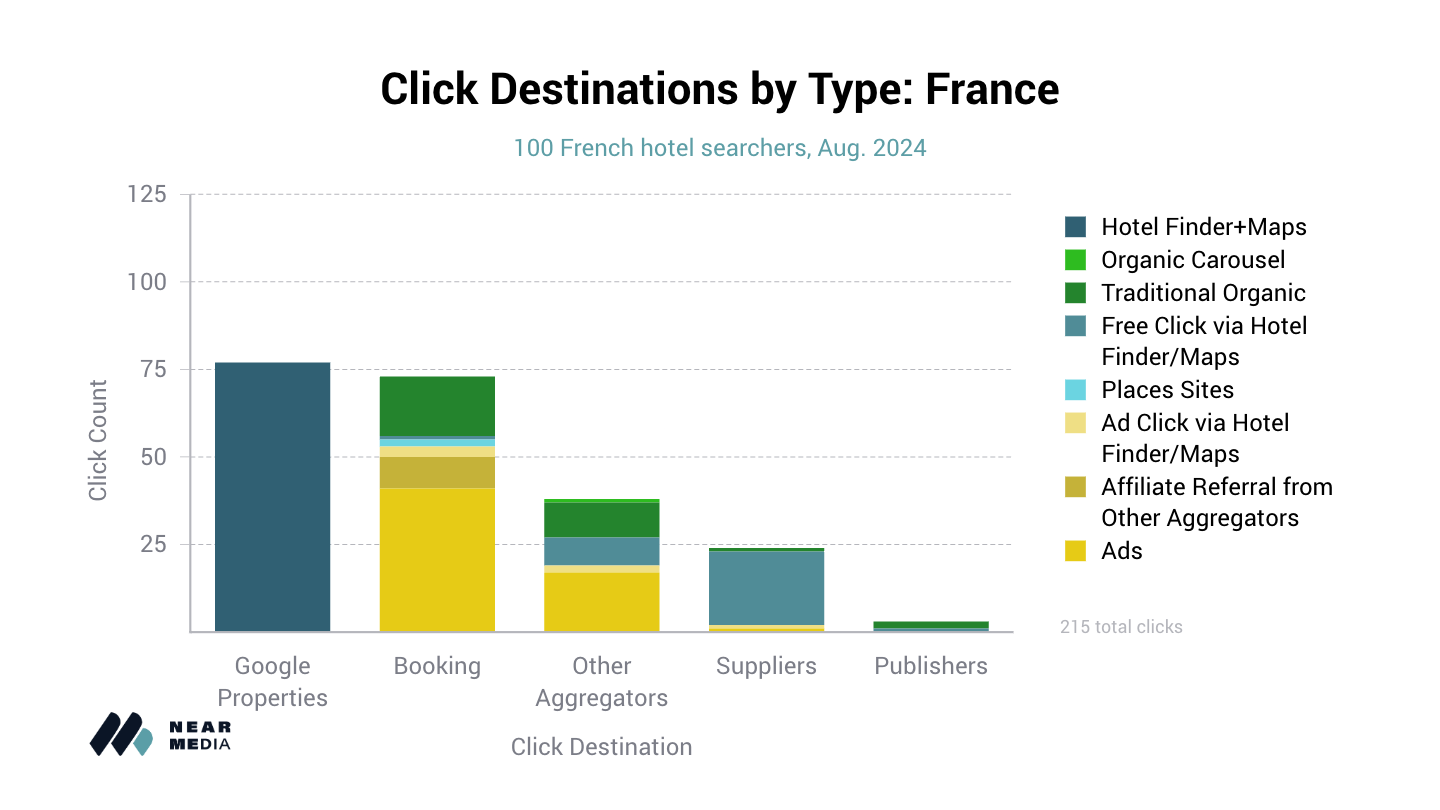

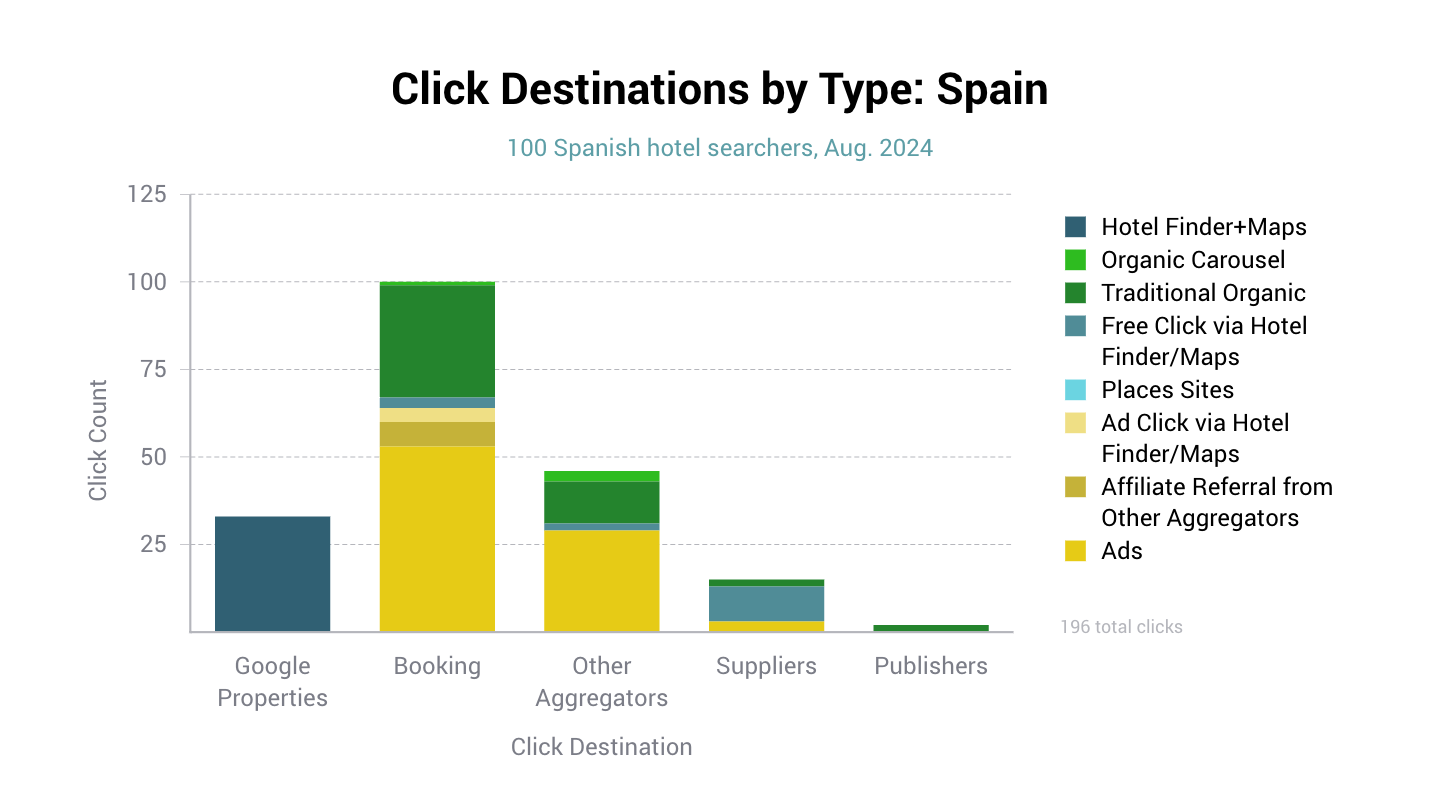

We saw different behaviors across German, French, and Spanish users in terms of their most common click destinations. German and French users were considerably more likely to engage with the Google Hotel Finder than Spanish users; Spanish users were the most likely to use Booking (though over 50% of search sessions in all three countries included at least one click to Booking). This is particularly noteworthy in the context of Spanish regulators’ existing fine of Booking for abusing its market position.

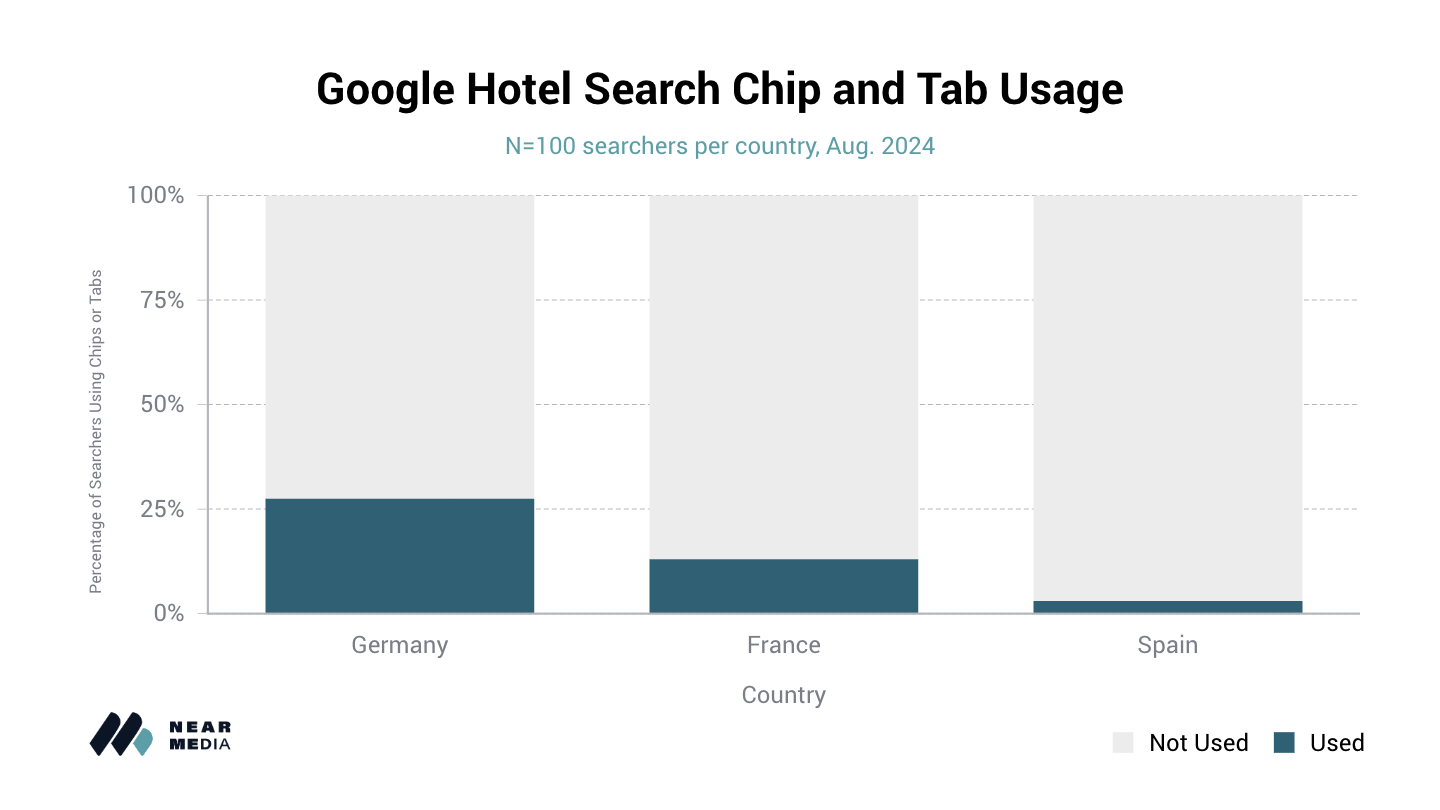

The primary reason for the difference in feature engagement is that French and especially German searchers were more likely to utilize the Tabs and Chips at the top of the Google SERP (most of which trigger prominent Hotel Finder results). Not a single participant out of 300 clicked the Places Sites refinement, however, and only 44 of 300 searchers across all three countries (14.6%) used any tab in their search session.

German searchers were also more likely to refine their initial query or queries–performing a higher number of total searches, and evaluating more results overall than their French or Spanish counterparts.

Where Searchers View and Book Hotel Properties

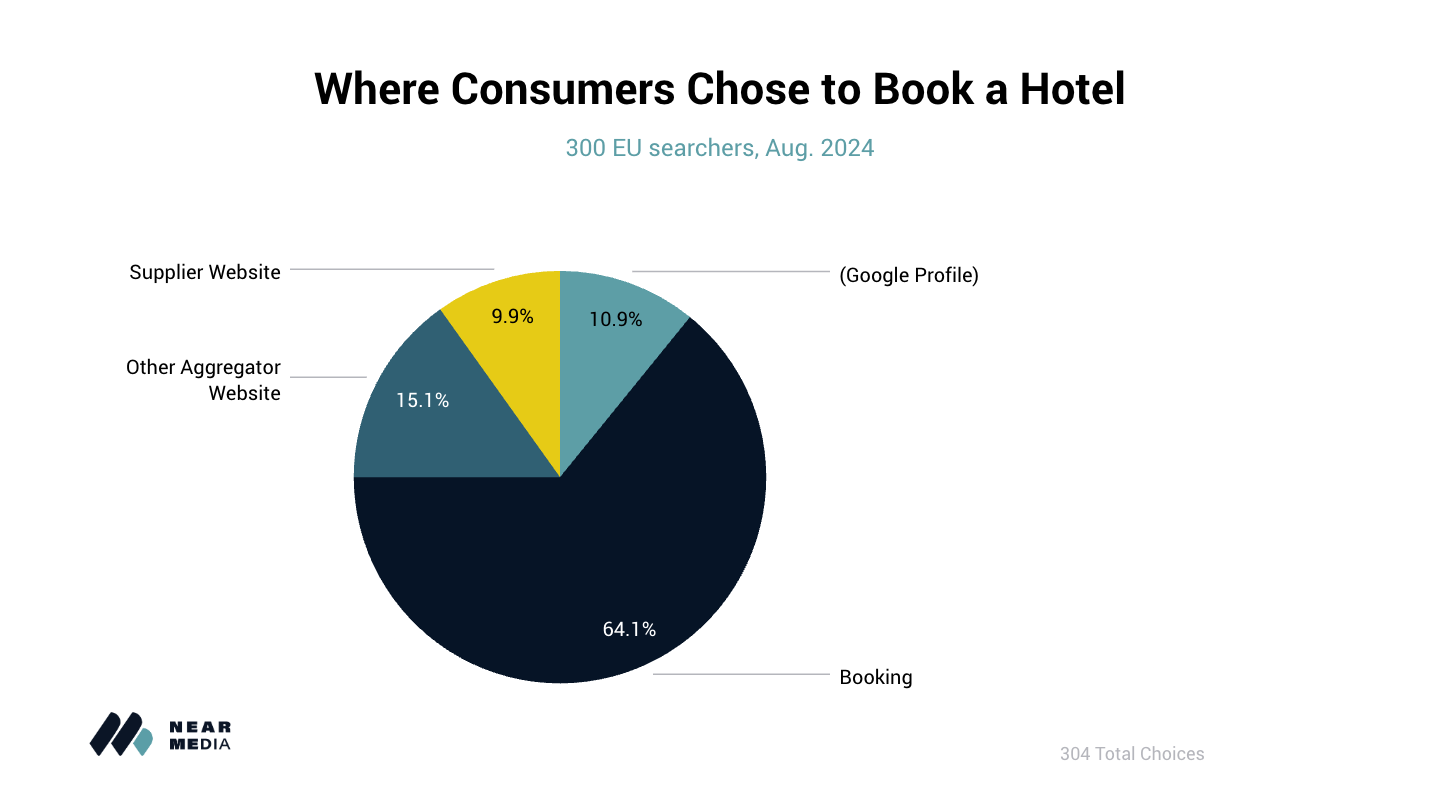

The consistent theme across all three countries was the tiny amount of traffic that Suppliers received, even after consumers considered all their options and were ready to book.

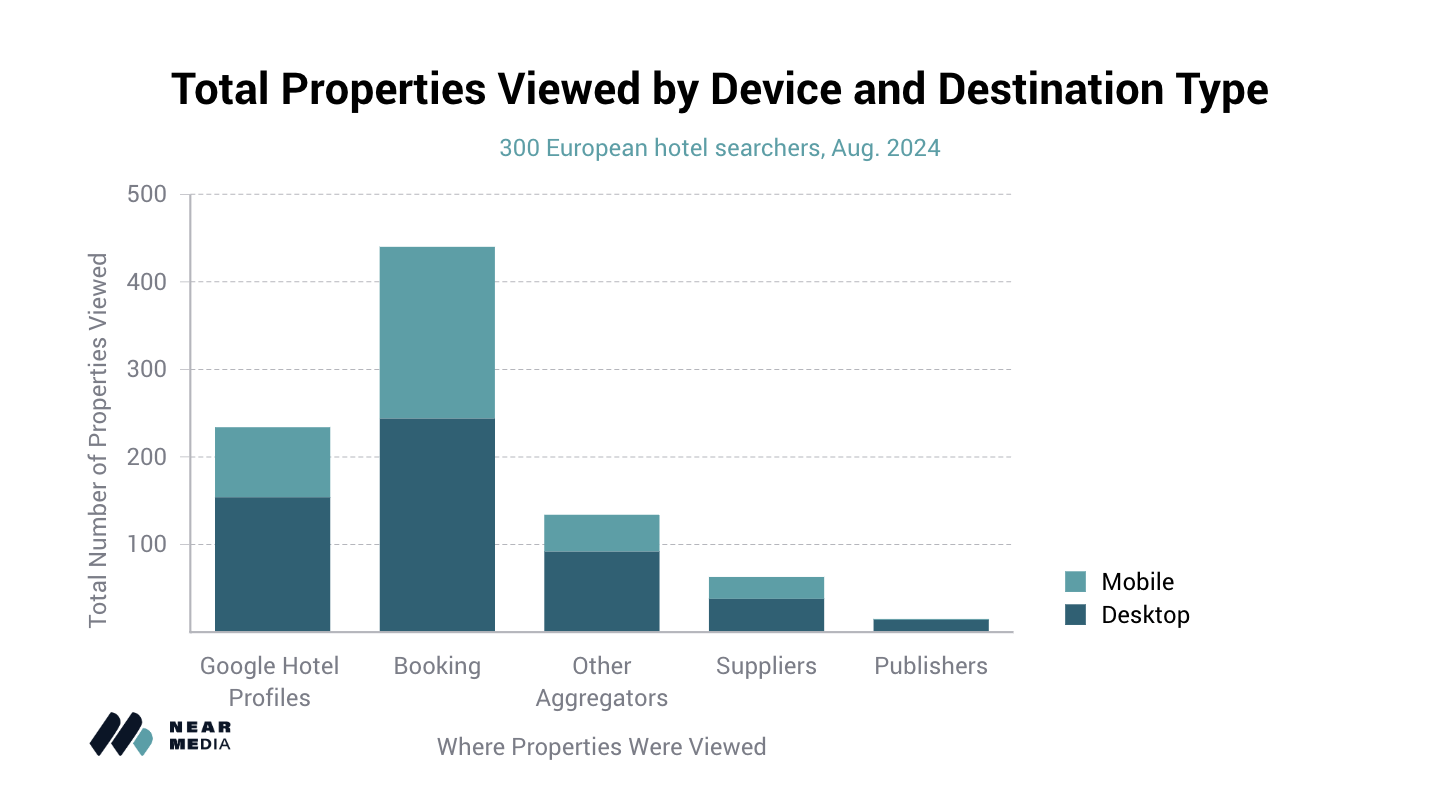

Only 8% of all hotels/rooms were viewed on Supplier websites (63/774 total), vs. 57% on Booking, 30% in the Google Hotel Finder, and 17% on non-Booking Aggregators. (Searchers viewed approximately 100 hotels/rooms on multiple websites.)

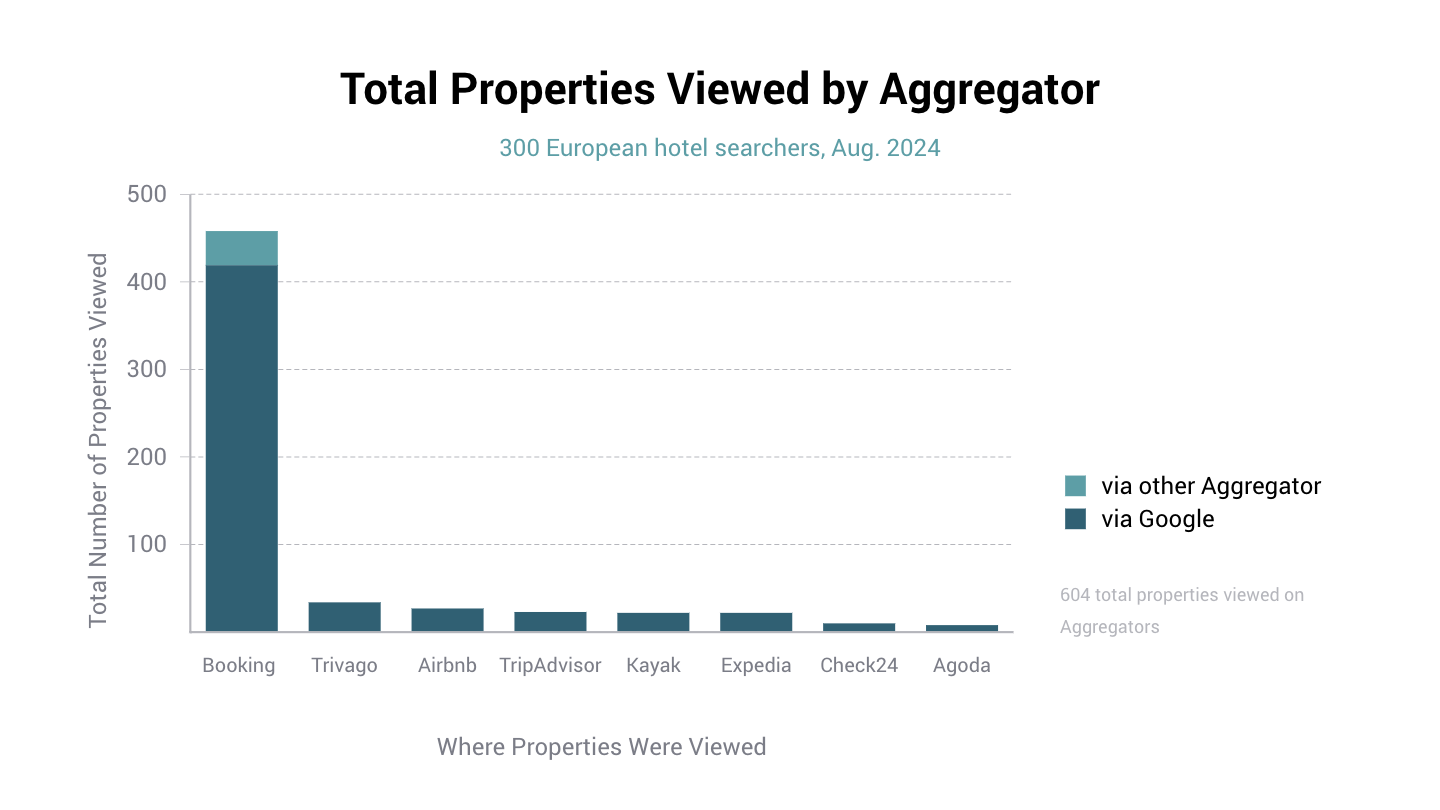

Booking completely dominates other aggregators in terms of number of properties viewed, and even drew a meaningful amount of traffic from other aggregators such as Kayak, Trivago, TripAdvisor, and others (presumably for an affiliate fee or revenue share).

As noted earlier, Google does send traffic to Suppliers’ websites from the booking section of its Hotel Finder Profiles, but when the consumer is ready to book, they frequently end up on an Aggregator website–many times, thanks to a fee paid to Google by the Aggregator.

In previous DMA workshops, Google has attempted to deflect responsibility for arbitrating the traffic battle between Suppliers and Aggregators. However, its aggressive monetization of hotel search relative to other verticals raises the ultimate price consumers have to pay for a given hotel room, no matter where they book.

Only 10% of searchers’ ultimate choice of room came from a Supplier’s website, whereas 64% chose their hotel room on Booking, and 14% on another Aggregator.*

* For obvious reasons, we instructed users not to make an actual booking, hence 11% of users completing the task while still viewing a Google Hotel Finder result.

Conclusion

We expected the results of this study to more-or-less match the results of our earlier search behavior studies in other verticals. They diverged in significant ways.

In European hotel search, Google’s own properties are less visible to consumers and receive somewhat less engagement from consumers relative to other local verticals, including restaurants in Europe and many U.S. verticals we’ve investigated).

That said, when it was visible to searchers in our study, the Google Hotel Finder still received a plurality of clicks, which is largely inline with our previous research. Also inline with our previous research, neither the Places Sites module nor the organic Aggregator Carousel introduced by Google in response to the DMA drove meaningful consumer engagement. And zero consumers in our study clicked the Places Sites refinement tab.

The impact of Google’s self-preferencing may be less noticeable in hotel search than in other local search verticals, but only because it is monetizing hotel search so heavily.

Consumers are far more likely to engage with Aggregator results in the hotel vertical than the others we’ve investigated – largely because Aggregators (especially Booking) are dominating Google’s paid search results. In many cases, mobile users in particular wouldn’t scroll past the first or second ad, one of which was usually from Booking.

We see one gatekeeper (Booking) enhancing its own dominant market position by paying another gatekeeper (Google) for premium placement. Both gatekeepers benefit, at the expense of the rest of the market, and neither has an incentive to change the status quo.

This is hardly a great outcome for consumers, who bear the ultimate cost of increased advertising costs paid to Google, and increased transaction fees paid to Booking, in the form of higher room prices.

Relative to other local search verticals, the results of our investigation into hotel search suggest that if there is a strong Aggregator in a given vertical, consumers will make use of it.

But by monetizing queries so heavily, and showing its own Hotel Finder results so prominently, Google has made it increasingly difficult for less-entrenched Aggregators (let alone Suppliers) to gain traction when it comes to capturing hotel bookings.

September 20, 2024

Data on the percentage of searchers making use of chips and tabs was added to the Chip and Tab section of this post, following the news that Google's latest proposal to comply with the Digital Markets Act centers around tabbed navigation options.